02

“Hey! Can you help dress this wound?”

“Emergency patient incoming!”

It was my first day at the university hospital,

a place where emergency patients and regular patients alike flooded the halls.

Especially in thoracic surgery—every operation was high-stakes,

the kind of cases most med students dreaded.

I was the only first-year resident in this department.

Which meant I had to move faster, handle more,

even though it was just my first day.

“What brings you in today?”

“Lately I’ve had sudden shortness of breath, my heart races, and I think I’ve had a bit of a fever…”

“Can I take your hand for a moment?”

As the patient listed their symptoms,

I noticed a bluish tint on their lips.

It immediately made me suspect cyanosis,

so I asked for their hand.

Sure enough, even their fingernails had turned blue.

Cyanosis: A bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes,

often suggesting cardiac or pulmonary disease.

“You’re showing signs of cyanosis.

That could mean a heart or lung issue.”

“We’ll need to do an EKG and a chest CT scan.”

“We’ll get those done and go over the results with you afterward,

so try not to worry. We’ll take good care of you.”

After seeing several patients,

I used a short break to check on the ICU.

More than half our department’s cases were emergencies or critical care,

so the ICU was packed.

I was checking on patient charts when a nurse urgently called out to me.

“This patient has a pneumothorax. Can you insert a chest tube?”

“Sorry, a chest tube insertion?”

“Yes, it’s an emergency.”

“…We should start with a chest X-ray.”

Chest tube insertion: A procedure to drain air, fluid, or blood from the chest cavity.

Chest X-ray: An imaging test of the thorax to evaluate heart and lung conditions.

Chest tube insertion was typically left to second-year residents or above,

unless under direct supervision from an attending.

But I was a first-year,

on my first shift,

with my first emergency patient,

and this would be my first chest tube insertion.

I had watched countless videos—

but doing it for real was different.

Still, the patient was critical.

There was no time to wait.

Though not a major surgery,

this procedure—done under local anesthesia—should still be performed with a supervising physician.

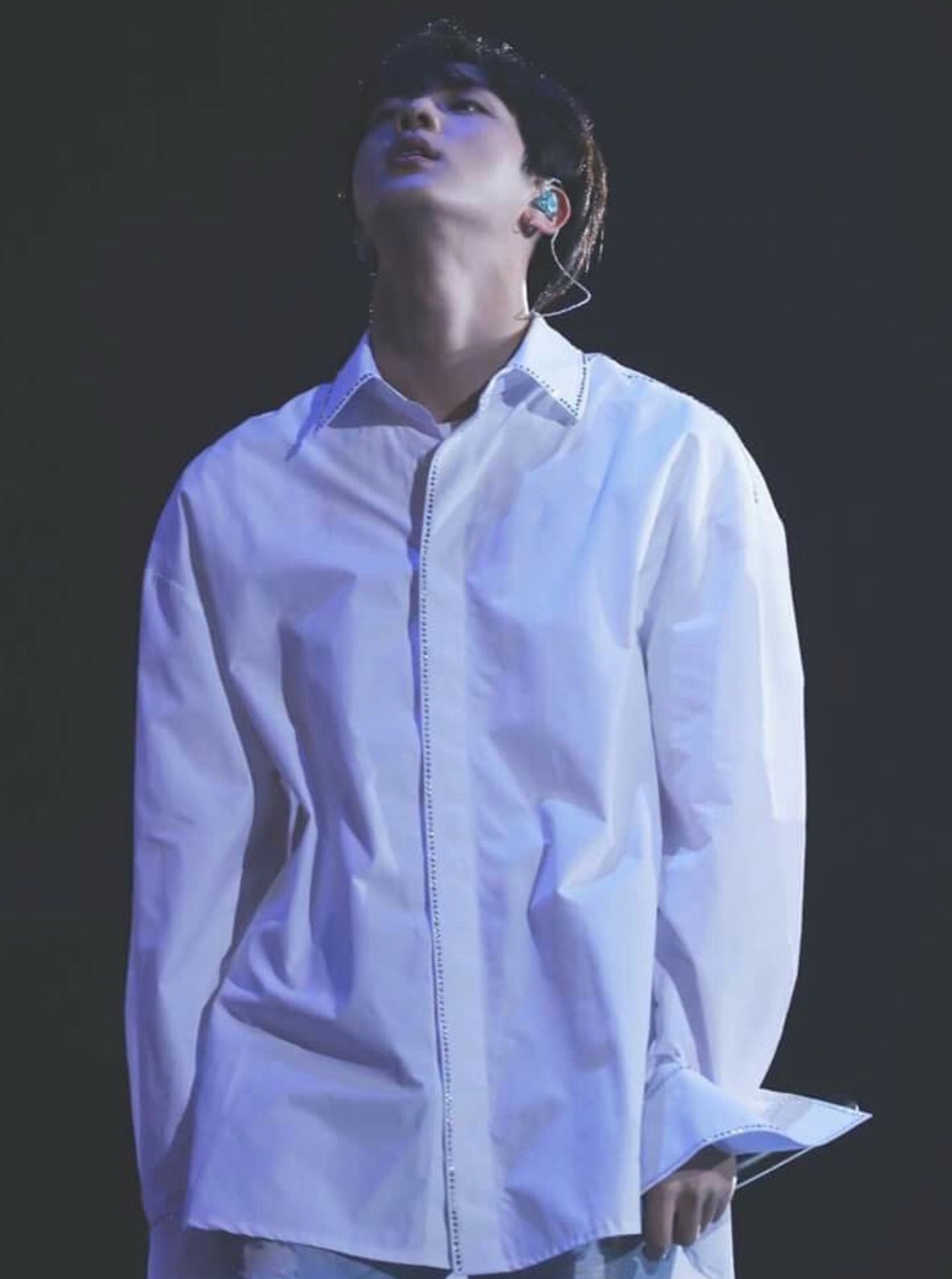

But Professor Kim Seokjin wasn’t around.

And I had to act.

Local anesthesia: A method that numbs a specific area of the body while the patient remains conscious.

So I did it.

I inserted the chest tube.

It seemed to go well.

No complications, stable vitals.

But whether it went well or not,

a first-year resident performing that alone was a serious protocol breach.

And of course,

news of it reached Professor Kim.

Soon, a voice like a blade cut through the air.

“Yoon Seo-ah.

Come to my office.

Right now.”